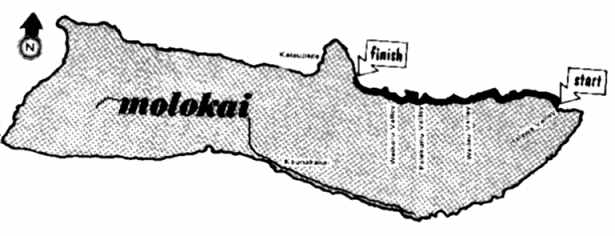

The north shore of Molokai is wild. Last month, two Lahaina men-school teacher Mike Shotzberger and photographer Peter Connally-made the unusual hike from Halawa Valley to the Kalaupapa Peninsula on this, Maui's neighbor island. The trek, along the uninhabited north shore, included five miles of swimming around areas where steep cliffs prevent any walking along the shore. This is the story of their trip.

Molokai

The Trek

BY PETER CONNALLY

The north shore of Molokai between Halawa Valley and Kalaupapa contains three deep, lush valleys named Wailau, Pelekunu and Wai kolu. These valleys today are completely uninhabited, except for island fisherman who camp occasionally in the summer months in Wailau and Pelekunu.

Not more than 150 years ago this coast was heavily populated with Hawaiians. Pelekunu Valley alone is estimated to have had a population that ran into the thousands.

We walked the shoreline from Halawa to the cliffs above Kalaupapa. It took five days to traverse the 17-mile coast.

The only existing means of getting into any of these valleys on Molokai are three: walk and swim the coast; climb 4,000-foot moss covered perpendicular palis in the back of the valleys, or come in a small dependable boat. There's a fair amount of boat debres along the coast that makes a convincing agrument for reliable engines.

Hiking is now discouraged by all authorities. The already busy Molokai Fire Dept. has had to go into this area several times this year on a rescue mission. One appearently experienced hiker has been missing since spring. His disabled partner had to be evacuated by helicopter. So, rather naturally, it's hard to get the necessary permits to cross rights-of-way, watersheds, etc. But the area can be entered legally by boat or by a walk/swim.

The shoreline of Molokai required swimming in six places for a total of about five miles. In numerous places, even at low tide, it is necessary to wade between large boulders fallen from the steep over-hanging cliffs.

There were some abalone-sized opihis in these areas. But if you wanted to get them, you had to be careful to keep one eye on the incoming surf and one eye on the slick, sharp rocks. Cliffs in these areas were often over 1,000 feet high, and overhanging in places. The incoming tide, and little bits of gravel and sand falling from above, hastened us on to safer opihi grounds.

And there were plenty of opihis, plus hihiwai (fresh water shellfish), opai (shrimp), crabs, fresh water and ocean fish. Goats are everywhere and pigs are in the backs of the Molokai valleys. Waikolu Valley has wild dog. Guavas and mountain apple provided amble fruit.

There were many sturdy Hawaiian terraced taro patches, full of taro now gone wild. There's a koa forest in the back of Wailau. These valleys haven't been touched by man since the Hawaiians abandoned them for a changing culture.

But desolate these valleys are not. It must be the getting there that's desolate. Perhaps, though, the term dosolate reflects a cultural bias. Hawaiians lived there in a stone age culture, but we modern men call the area desolate. Ane desolate it is: desolate of high-line wires and telephone poles, of cars, roads, buildings and concrete. The area is "desolate" because it defies change by technological man. It would be a feat of engineering just to get a piece of heavy machinery into one of those valleys. I just hope no enterprising developer takes this as a challenge.

Reguarding development, the State of Hawaii is the major land owner in the area. There lands include the Kalaupapa Peninsula and all of Waikolu Valley. This area is presently being used by the State Dept. of Public Health for a Hansen's disease settlement. This settlement is in the process of closing. The question now is what the State will do with the land.

It's not too far in the future for the patients of Kalapapa to be thinking about this subject. Rumors of unwanted development exist among the population of the settlement.

The future is unknown, but it will be fast upon us. Hawaii has several options requarding the Ko'olau, or windward, coast of Molokai.

l. Through the current developer-oriented Land Misuse Commission, the State can sell-out to development.

2. Some or all of the land can be returned to the Hawaiian people to till and fish as their ancestors did. It is doubtful if that many people would be willing to do this now, because of cultural conditioning to Western Civilization. Transport makes the possibility of profitable agriculture and fishing very slim. But for subsistence purposes, it is ideal.

3. The present patients of Kalaupapa should be given an option on fee-simple house lots. Kalaupapa now is their home and it would be as hard for them to leave as it was to come there in the first place.

4. A State or National Park can be established along the lines of the Kipahulu Reserve in Haleakala National Park here on Maui. It would be a semi-restricted area; no autos, helicopters, concrete, hotels. An area where one could continue to sense the natural environment of ancient Hawaiian culture.

This Ko'olau district stands as a monument to the Hawaiian race. It defies change as if protected by a kahuna's spell. It is there to enrich our lives with an increased consciousness of the heritage of Hawaii.

To Go To Maui Sacrificial Temples Update-Click Here

To Go To Return Kahoolawe-Click Here

To Go To Hawaiian Printing-Click Here

To Go To Maui Bike Path-Click Here

To Go To Sierra Club-Click Here

To Go To Sacrificial Temple-Click Here

To Go To Money-Click Here

Maui Lahaina Sun

Buck Quayle at the Maui Lahaina Sun bureau circa 1970

Reporter/Photographer Buck Quayle in 1971 in Maui with the Cartagenian in the background

Buck Quayle, 2011

Hawaii

Another Day At The Office Haleakala National Park

Tiki

Whale tail